Grand Teton to West Yellowstone - Ski Traverse

On February 18th, I set off alone with a 60-pound sled and a 20-pound backpack – prepared for up to 12 days in the wild, traversing Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks, solo and unsupported. I chose my gear to withstand heavy rain and snow, gale-force winds, and temperatures in the realm of -40F. Skiing directly to the front doors of the Wild West Saloon in West Yellowstone for pizza and cold frothies on Friday, February 26th, the trip was complete! This expedition and my ‘Montana Top 50’ trip are undoubtedly the most influential, memorable, and cherished single-push wilderness adventures of my life – hands down.

Topographic Image of Ski Traverse

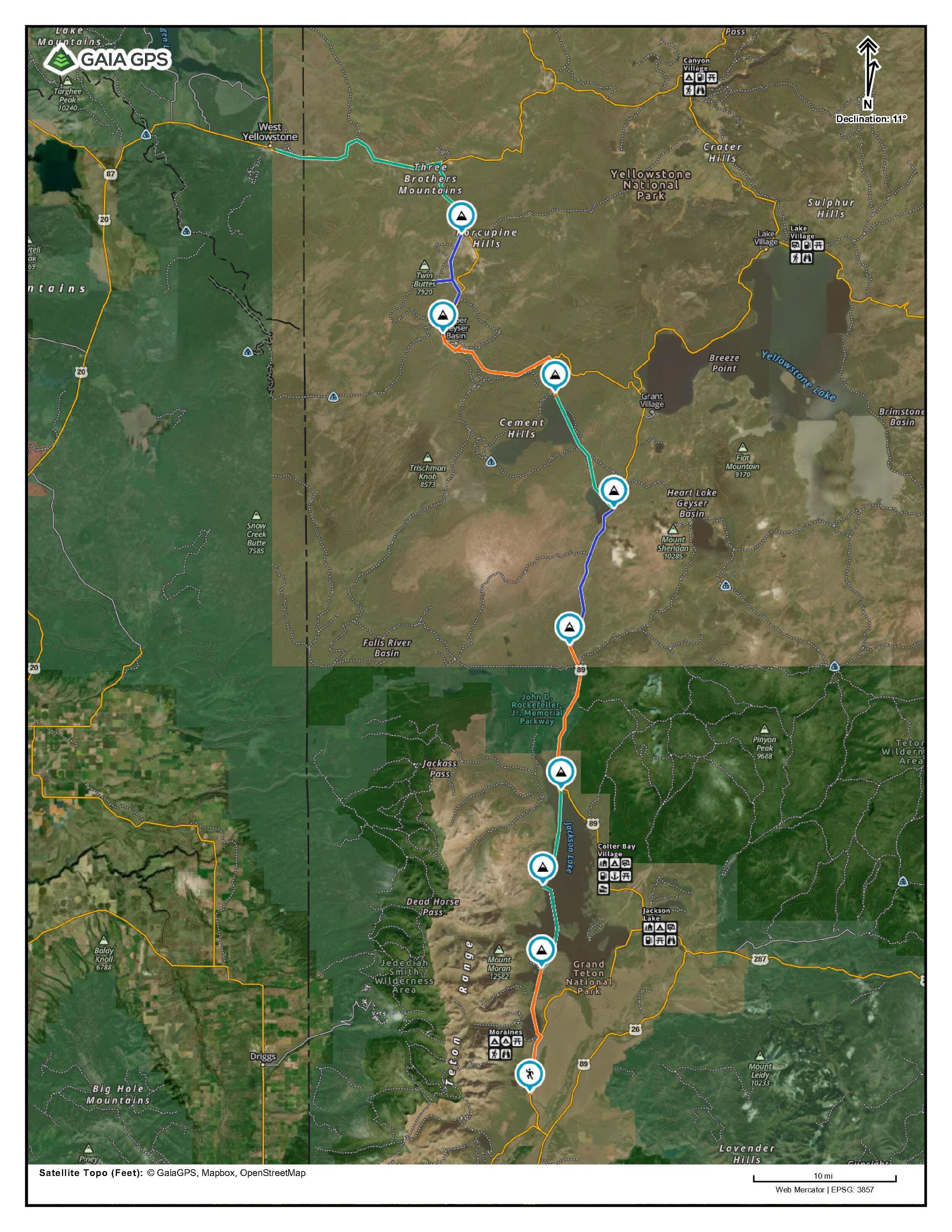

Satellite Image of Ski Traverse

I had the opportunity to experience a wide variety of snow conditions, navigate drainages and partly-frozen waterways of varying thicknesses, use snow bridges to cross hydrologic features, and observe the world frozen in time and silent – entombed rushing rivers and suspended waterfalls.

During the day, I was hypnotized by the repetitive sound of my skis moving through snow and my deep harsh breaths.

The soothing tinkering of snow on the roof of my tent often lulled me to sleep at night, and I woke to the sun slowly rising to the east. Almost more than my physical and mental preparation - the ability to adapt to the ever-changing climate and terrain, manage route changes efficiently and methodically, and appropriately react to non-stop curveballs is paramount to coming out the other side intact.

Sled dragging through the snow near the base of the Grand Teton. This toboggan can be found at most hardware stores, equipped with two ½” PVC poles in an ‘x’ formation to my backpack hip belt worked like a charm. NRS straps and paracord loops installed held the gear down tight. A 30L ski-mountaineering pack was used.

Route and Climate Challenges:

I encountered a deep snowpack from the start: ongoing persistent precipitation, unforeseen sluggishness, and extra-laborious travel. After three days of the expedition – I changed my route completely – living a day-by-day approach to my course and forward progress. I strategically utilized the groomed (not plowed) arterial highways within Yellowstone Park for faster miles and easier navigation.

Following the trip, I spoke with a veteran ranger of Yellowstone National Park who confirmed that the snow and climate conditions encountered during this expedition’s week and a half time frame was “undoubtedly the most arduous of the year.”

Total snow accumulations during my 9-day adventure totaled more than 4 feet (the majority in the first half of the trip). I encountered persistent gale-force winds, daily sub-zero wind chills, and an ambient temperature range of -20F to 30F. With the second half of the trip yielding a cold snap, average ambient temperature lows were sub-zero daily.

“It’s not an adventure until something goes wrong.”- Yvon Choiunard

Day 4/9

3-hour marathon on the malfunctioning MSR Whisperlite stove – completely disassembling the pump and servicing the entire unit - maintenance on my impromptu surgery table. My hands and sleeping bag were lined with soot and white gas. Exhausted after fixing the problem, I skip dinner and go straight to sleep.

The three main factors that will make a trip easier or harder are the amount of current snow combined with current precipitation, temperature, and solar radiation. The Tetons hit a record for the top 5 snowiest February’s ever (inception of records date 1950’s or 60’s) – meaning it snowed a ton the first two weeks of the month before I started and the week and a half that I was out in the elements.

Additionally, the temperature never rose above freezing, and the sun rarely came out – not giving the massive fluffy snowpack a chance to settle.

Navigating by compass in a full whiteout

Together with my self-built pulk, I ski traversed six lakes, encountered both deep slush and impenetrable crusts on lakes and rivers, debilitating snow glop on my skins, a failing stove, and a broken tent pole. I nearly ran out of fuel (white gas) and had to figure out how to resupply. Moreover, I had moisture and condensation issues in my tent, sleeping bag, and apparel and finished the expedition with minor frost damage to both my hands and feet. During the 9-day trip, I encountered no other human foot traffic.

My route alteration resulted in a scenic tour to Old Faithful, where I was spontaneously allowed to enter the employees-only brewpub. Time indoors gave me a dry space and time to mend my tent pole with medical tape in a warm and dry environment and rejuvenate with some warm food and conversation.

Another essential detail to note is the elevation gain. My route of 110 miles totaled a mere 4,000 vertical feet of ascent throughout the entire trip compared to the Montana Top 50, which was 190 miles and had 105,000 feet of vertical gain. Even on gradual (<10% grade) slopes, breaking trail in deep powder with a 60-pound sled is unquestionably slow and physically taxing. The few short 10-25% grades I traveled through forced me to disconnect my sled and whilst holding the PVC poles, utilize the carabiners at the end of the poles to temporarily connect to small branches or the trunk of saplings to move my body position and skis forward by 1-2 feet per iteration.

Needless to say, I avoided uphill like the plague.

Substantial snow glop on skins and my sled filled with and continuously plowing snow behind me.

Wildlife:

A significant incentive for going on this expedition was to see what variety of wildlife I may encounter when I was in the wild. Coincidentally, in three days of Grand Teton National Park, I only saw two raptors flying near the top of the trees. I wondered why there were no significant tracks or visuals of mammal life.

A lone fox hunts at dusk.

As I traveled north, notably at about 70% of the route completion, the snowpack reduced dramatically as the terrain changed and the amount of thermal activity skyrocketed. Bison, foxes, coyotes, swans, geese, and ducks lined the rivers where the snow level was much less significant to get easy access to the vegetation on the ground surface or critters beneath a small layer of snow. One evening I watched a lone fox pouncing headfirst in the snow as it hunted for a meal. For several days, I watched hundreds of bison using their enormous heads to shovel snow side to side and expose the vegetation for a non-stop buffet. They stared at me silently with frost-covered coats before bedding down in the same ranges that they fed.

These extended duration trips (including the Montana Top 50) allow me to slow down and observe the natural world – both viewing it in a different light and allowing me to cover distances unfathomable in an extended weekend.

“I dream of a hard and brutal mysticism in which the naked self merges with a non-human world and yet somehow survives still intact, individual, separate… I am twenty miles or more from the nearest fellow human, but instead of loneliness I feel loveliness. Loveliness and a quiet exultation.” - Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire

A coyote struggles up the steep hillside in deep snow

Bison grazing near thermal features

As I begin to write, each finger and portions of my feet are losing circulation due to frostnip incurred during the expedition. Breaks are required to warm my hands in my pockets and move my toes to facilitate blood flow. The extremities will recover fully over the next couple of weeks. Frostnip may have been inevitable due to the extreme cold temperatures in the second half of the trip and specific moisture problems that occur with long-duration winter expeditions. Drying gear becomes incredibly difficult when items become wet – significantly when the sun rarely exposes itself, and the temperature does not rise north of freezing. In true winter, “what gets wet, stays wet.”

Garmin inReach Mini showing the low of -18F

Blisters on my swelling feet were beginning to form by mid-day on the first day, though they have healed rapidly! Each morning upon waking, I methodically administered first aid (bandage dressings and vaseline) on my feet to reduce the rate of damage incurred.

The scope of learning for these expeditions goes beyond that of navigation, climate observations, risk management, pacing, nutrition, etc. – the learning also includes the experiential value of injury and treatment. As such, I am glad to have sustained and managed these injuries throughout the trip. This will prove invaluable in future projects and help me set better thresholds to differentiate and evaluate the combinations of discomfort, fatigue, pain, and injury.

Ice ‘cobwebs’ (ambient temperature -20F) forming inside my tent on the coldest morning. It took me 45 minutes to put my pants and jacket on. Bumping the side of the tent would release ice formations on me and melt.

Jackson Lake:

Day 2 yielded the lowest mileage day of the entire trip, only 6.5 miles. The prior night and morning produced nearly a foot of fresh snow, compressing the ice formation on Jackson Lake as I entered. I would soon learn that Newton’s third law applies in this situation – every force has an equal and opposite reaction. When the lake ice is loaded with a substantial force, the force of the new load displaces liquid. Water rises around the lake’s perimeter, which is released onto the top of the lake.

Guess what the result is? Deep slush underneath a layer of snow.

A shovel-head (10”) of standing water more than ¼ mile from the shore of Jackson Lake. You can see my slushy footprints near the small excavation. Good thing I had closed-cell foam boot liners that help prevent the absorption of moisture.

Jackson Lake, only 10 miles in length, took two full days to cross. Day 2 and 3 were undoubtedly the most difficult days of the trip. Interestingly, there were among the most memorable as well. Substantial periods of the lake crossing were nearly in or entirely in a whiteout. The microscopic breaks in the clouds, heavy snowfall, and gale-force winds on the lake (blowing snow) created visual misrepresentations of my surroundings and nearby landmass. At certain points, I was disoriented enough to feel as though I was hallucinating. To combat the minor visual hallucinations, I would close my eyes for periods of time to challenge myself to move in as straight of a line as possible.

“When things are easy, I hate it.” - Earnest Shackleton

Near the end of Jackson Lake in a complete whiteout, gale force winds, and a wind-scoured face

Wind scoured face and melting ice-beard – relieved to complete the Jackson Lake at dusk! Time for some hot tea.

Hydration and Fueling:

I wildly underestimated the challenge of eating and drinking during the entirety of the trip. I’m more accustomed to spring, summer, or fall excursions (or short winter excursions), where specially designed running and fastpacking backpacks have storage capacity for my phone, water, and 1000 calories on the shoulder and waist straps of my bag. That utility storage was extinguished with the more technical ski-mountaineering pack. My insulated camelback hose was frozen solid 99% of the trip. As such, intaking water would require disconnecting the sled from my backpack (2 carabiners), taking off my pack, opening, and rummaging through it.

While that may not sound terribly inconvenient, stopping for more than a few minutes when ambient temperatures are 0 degrees Farenheight or the wind is feeling passionate results in full-body shivering, tightened muscles, and likely numb fingers and hands.

The cold was undoubtedly a genuine motivator to keep moving as opposed to my Montana Top 50 trip, where I could sit and throw a marvelous 1-person pity party whilst casually sitting on a rock in the warm sun with a cool breeze.

Caloric intake took a similar flavor. I could keep calories in my internal and external jacket pockets, but I’d have a better chance of winning the lottery than opening a ziploc with -20F rated Sasquatch-sized gloves. At times, even my Clif bars froze, and GU gels turned to GU slushies on the coldest days.

History - 1988 Fire and Lodgepole Regen:

During the year 1988, roughly 1/3 of Yellowstone National Park’s 2-million acres burned. The series of fires burned hot due to the extensive lodgepole, spruce, and fur trees within the park and the serotinous cones from the lodgepole seeded. Serotinous cones are activated to open during extreme heat from melting resin, which is transported by wind and gravity. While the fires decimated the landscape in 1988, the lodgepole saplings have rematerialized and dominated a large part of the park in the last ten years.

After the Lewis River no longer became navigable due to thawing – took to the forest and was forced into the 1988 regen area. On Gaia Maps I saw ‘Dogshead Trail’ which I had no information on and gambled with the possibility of easier travel. I also knew if the trail was maintained, it would likely be easy to follow since the trees were so thick. The gamble was fruitful!

Due to the number of cones that released seeds, significant areas of the park have “impenetrable” walls of young lodgepole (30-40 years old). I feel like I’ve earned a strange and generally unwanted bush-whacking badge from my off-trail projects around the United States and abroad – but I’ve never seen anything like the Yellowstone lodgepole walls. Surprisingly the size of the trees wasn’t debilitating, but the quantity and density of the 1 to 5-inch diameter and 10-foot tall saplings half-buried in the snowpack proved different.

Thankfully, I had the opportunity to experience navigating a reasonable amount of this landscape without having too much feel frustrated and burned out.

And now, I am spending time both recovering and plotting my next escapades in the mountains. I will continue to take time to reflect on this trip and my excitement simmers for the next.